Boundaries: A Construction of the Self Pdf

INTRODUCTION

Boundaries is a rich and complex subject as there are boundaries at every level of our existence. We will explore a few aspects of the self and boundaries, with an additional focus on using our boundaries to enrich our lives. Boundaries are sacred and deserve respect, but boundary violations occur all the time, to varying degrees of destructiveness. Boundary violations do damage to the self and need healing. This newsletter lays the groundwork for future discussions.

As we understand what boundaries are, we can then consciously (with awareness, “mindfulness”) create, dissolve, open, and close our boundaries in ways that can create a fulfilling life for ourselves.

Point of Empowerment: Loving relationships are built by relaxing our boundaries and on occasion, dissolving them. We form a “we” out of an “I” and a “you.”

Practice: Develop an understanding of boundaries and the skill of using your boundaries, to create loving relationships.

DEFINITION AND FUNCTION

A boundary is a barrier that separates. The boundaries of our self shape and define who we are. Without our boundaries we would cease to exist. We have physical, mental and emotional boundaries. Let’s consider some examples of our boundaries, which will help us understand what they are and how they function. (To function means to “do its job.” For example, the heart’s function (“job”) is to pump blood throughout our body.)

Physical Boundaries

Physical boundaries involve our physicality. For example:

- Our skin separates what is outside of our body from what is inside, allowing us to maintain our physical integrity.

- Our skin is the boundary that separates “me” from “not me” physically. It helps us to define “who I am” and “who I am not.”

- The organs of the body have membranes that separate them from their surroundings. This is the only way they can continue to function. The membrane of the heart keeps it separate from its immediate surroundings preserving its integrity as a heart.

- When self-control of our behavior functions as a physical boundary it sets a limit (boundary) as to what we will and will not do.

Mental

Mental boundaries involve our brain, mind, and thinking. For example:

- The brain functions as a boundary when it sorts through all the information available to us from our senses, only allowing some of that information into our awareness. This keeps us from being overwhelmed by all our sensations and perceptions.

- We create a mental boundary when we “change our minds,” shifting from an old way to a new way of thinking. This allows us to grow through changes in our thinking.

- Learning a new way of seeing things, changing our perspective, sets a boundary between an old and a new way of perceiving the world. As we perceive the world in new ways we create new experiences for ourselves.

Emotional Boundaries

Emotional boundaries involve our emotions and feelings. But what is the difference between emotions and feelings? Most of the time we use these words interchangeably. Let’s make a distinction: feelings are felt sensations that occur in our body; emotion (e—motion, energy in motion) is the combination of thought and feeling to form a synergy (something that is greater than the sum of its parts). Emotions give rise to our impulses to act.

Our feelings arise spontaneously and have a natural flow. They have a beginning, middle, and an end. Since our feelings are our experience of life, we try not to limit them. We do not want to put up boundaries against our feelings, though we may limit the expression of our feelings toward others. However, there are many times with we use our “defense mechanisms” to limit “unwanted” feelings.

The distinction of “Me and not Me” enables us to create emotional boundaries. As we interact with other people, we sometimes take in their feelings making them our own, acting as if they belong to us.

For example,

- My friend has just been insulted. Feeling her anger as though it was my anger, I start to “fight her

fight,” the “fight” that belongs to her (which is different than defending my friend).

fight,” the “fight” that belongs to her (which is different than defending my friend). - My boss yells at me when I make mistakes. I feel inadequate, calling myself an idiot when this happens, even though I sense that he has his own problems that he is taking out on me. I need to say “no” (at least to myself) refusing to make my boss’s frustration my own, understanding that his feelings don’t belong to me. Also, I do not direct his anger against myself by calling myself a name. I probably feel my own anger at him for mistreating me.

The process of “taking in” (internalizing) another person’s feelings, is very destructive because we cannot work with these feelings, and get “stuck with them” inside us. It is like eating something that is so heavy, we can’t digest it, and it just sits in our stomach. Here is where the sense of “me and not me” is a crucial emotional boundary that allows us to keep feelings that do not belong to us “out.”

Here is an example of the interplay between mental and emotional boundaries, and the lack of personal boundaries between spouses.

- In anger, my spouse blames me for our child’s school problems. I also blame and get angry at myself even though I think I am not the only one responsible. In blaming myself and feeling responsible, I feel guilty. I do not say “no” (do not disagree), to set a boundary between my beliefs and my spouse’s beliefs. I therefore feel confused. Creating a mental barrier by clarifying what my beliefs are, would diminish the guilt, anger, and confusion that I feel.

DEFENSE MECHANISMS

Our defense mechanisms are mental/emotional boundaries that keep certain thoughts, feelings, and perceptions out of our awareness. We deny their existence and banish them from our consciousness. Denial is the primary defense mechanism. It is a statement to ourselves that what we truly see, hear, think, or feel, does not exist. At the time of making this statement, we think that this is a necessary thing to do, but it is a destructive process because in denial we screen out important aspects of our life. In step two of using our defense mechanisms, we employ a secondary defense mechanism. For example:

- I am furious, very angry, at my friend, but deny my anger because “I am not supposed to feel that degree of anger.” I project it thinking that my friend is very angry at me. Now he/she has the anger not me. However, the reality is that I am furious, but in denying and projecting it (the defense mechanisms), I have lost a piece of me, my feelings, and weakened my ability to be aware.

- Someone said that one of my favorite politicians took a bribe. I like him very much, believe in what he has said, and voted for him, (even though he had been arrested). I don’t believe it. I deny the fact that he could do this, and explain the report away by saying that someone in the opposition must be framing him.

These are relatively simple examples of the use of defense mechanisms. Our use of them, in our internal life, is usually much more subtle and difficult to detect.

Practice: Be willing to look inside yourself, considering the idea that you are in denial of aspects of your external and internal world, of your perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. For example, start your day with the affirmation, “Today I will become aware of something I deny,” and be attuned to (aware of) new thoughts and feelings that create some degree of discomfort. Acknowledge (state to yourself) what you discover with the statement, “Aha, this is something that I have been denying.” Write it down. Congratulate yourself.

FORMING BOUNDARIES, HEALTHY AND DYSFUNCTIONAL BOUNDARIES

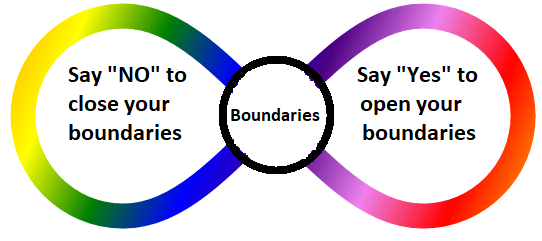

We construct and use, simple and complex boundaries throughout our lives. We begin to develop our boundaries at two years of age when “no” is the most important word in our limited vocabulary. “No” and variations of no (“stop,” “this does not work for me,” “I won’t continue,” “please don’t,” “I can’t agree to that”) set limits. “No” keeps out what is unwanted. We close our boundaries and protect ourselves.

Point of Empowerment: “NO” is the boundary setting word. Learning the skill and art of saying “No” is a lifelong task.

On the other hand, “Yes” opens our boundaries and lets in aspects of our world that we need and want. We let in the external world in. Examples of the external world are air, food, and sensations (sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell). In our relationships with the people in our life, we open ourselves to everything that person “sends our way.” We also open ourselves up to perceive the vastness of our internal world, composed of thoughts, feelings, desires, needs, expectations, and the products of our imagination—images, wishes, dreams, and fantasies.

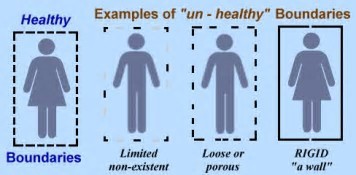

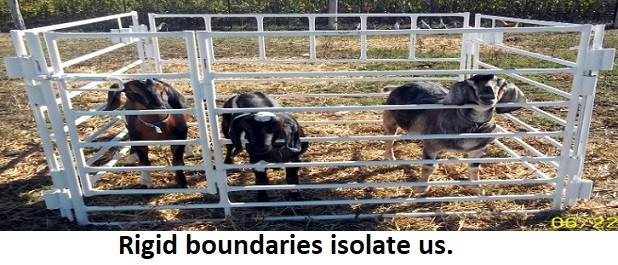

Healthy boundaries are flexible, opening and closing, becoming thick and thin, as appropriate to a situation. Dysfunctional boundaries are rigid/inflexible and too “thick” or too “thin.” “Thick headed” and “thin skinned,” are two common phrases that refer to boundaries that are too thick or too thin. Rigid, too thick boundaries wall us off from aspects of our self diminishing our experience of life. They restrict the use of our abilities, restricting our ability to cope with life. Rigid, too thin boundaries do not protect us as they are easily broken through or shattered. Some examples:

- This boy I like has been asking me out on a date. I refuse to go out with him, and will keep saying

“no,” because I am terrified of letting in the feelings I have for him. I put up a rigid boundary against him and against my feelings.

“no,” because I am terrified of letting in the feelings I have for him. I put up a rigid boundary against him and against my feelings. - I don’t want to agree to do what my mother is asking. I know that it is wrong for me, but since she keeps asking I will eventually say yes. My boundary is weak and thin. I can’t say no to her.

- I have agreed (said “yes”) to go where my spouse wants to on vacation, but next year I will insist (say “no”) that we take turns, and go where I want to go. My yes and no are flexible boundaries that facilitate the well-being of our relationship. Here “no” and “yes” function at the boundary between the internal world of our desires and the external world of our relationships with others.

- I do not answer the telephone (“saying no to the phone”). This sets up a boundary (a barrier to communication) in the relationship I have with someone I do not like, who keeps calling me.

These relatively simple examples illustrate how “No” and “Yes” function in our daily lives to set boundaries.

Boundaries of the self and the self as a

system (boundaries required), are fully explored in

The Operating Manual for the Self.

THE ART AND SCIENCE OF USING OUR BOUNDARIES

Using our boundaries is a science because certain actions almost always produce certain results. (For example, saying “no” at the right time builds your self-esteem.) It is an art because knowing how to proceed is not always clear as there are many possibilities and choices in ways to set boundaries. In the December newsletter we will apply the process of using our boundaries to have more pleasure and enjoyment, and less pain and stress, during the holiday season. This will illustrate how the conscious use of boundary setting can add fulfillment to our lives.

IN CONCLUSION

We have seen how important boundaries are as an aspect of every moment of our life. Developing the skill, then the mastery, and finally the artistry of using our boundaries enables us to create a rich and rewarding life.

Let’s unite in developing our human potential. Share this newsletter with others. Please visit our website, IIFSD.org. We invite you to participate, (as suggested in the Participation Menu selection). When you buy The Operating Manual for the Self (manualfortheself.com), you support our vision and mission. When you read The Operating Manual for the Self, you leap forward in your personal self-development and evolution.

Copywrite IIFSD.org, 2017. All rights reserved.